Contributor author to Circular Berlin:

Piyush Dhawan , German Chancellor Fellow 2017-18 working on the topic of Circular Economy and Circular Cities.

Parag Khanna, in his book Connectography has beautifully written that “cities are mankind’s most enduring and stable mode of social organization, outlasting all empires and nations over which they have presided”. In the 21st century, cities have become the world’s dominant demographic and economic clusters, and they certainly deserve more nuanced treatment on our maps than simply as homogeneous black dots (Khanna, 2018). Today, we live in a world where there are far more functional cities than viable states. By 2020 our civilization shall witness and live with the first cohorts of the Generation C (“C” for connected) and we need to think of cities that could cater to their aspirations (Puutio, 2018).

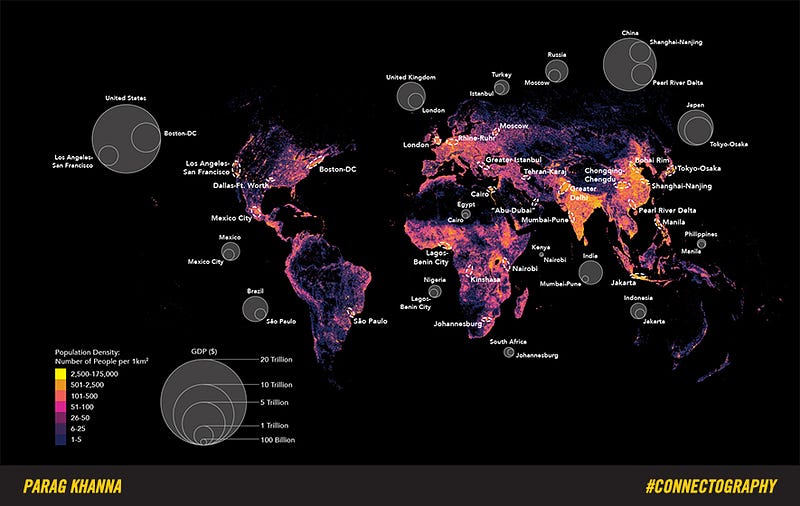

The map above from Connectography shows the distribution of the entire world’s population, with the bright yellow representing the densest areas. These zones are, not surprisingly, where you find the dashed ovals that represent the world’s burgeoning megacities, each of which represents a large percentage of national GDP (indicated by the larger circles), in addition to its role as a global hub. Within many so-called emerging markets such as Brazil, Turkey, Russia and Indonesia, the financial centres accounts for at least one-third or more of national GDP. In the UK, London accounts for almost half of Britain’s GDP. By 2025, there will be at least 40 such megacities across the globe. By 2030, the second-largest city in the world, behind Tokyo, is expected to be … no not China, but Manila in the Philippines.

From a resource viewpoint, Cities are also aggregators of materials and nutrients, accounting for 75% of natural resource consumption, 50% of global waste production, and 60-80% of greenhouse gas emissions (UNEP, 2013). It is expected that by 2050, 70% of the world’s population will live in urban areas. The future cities, while sustaining this population, must also become resilient to climate change, increase energy and resource efficiency, solve the existing social imbalances, and improve human well being.

The circular economy is one of the concepts that is gaining popularity at the urban scale, aiming to reduce the pressure on the ecosphere through a number of strategies. A circular economy is a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimized by slowing, closing, and narrowing energy and material loops. This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling. This is in contrast to a linear economy which has a ‘take, make, dispose’ model of production.

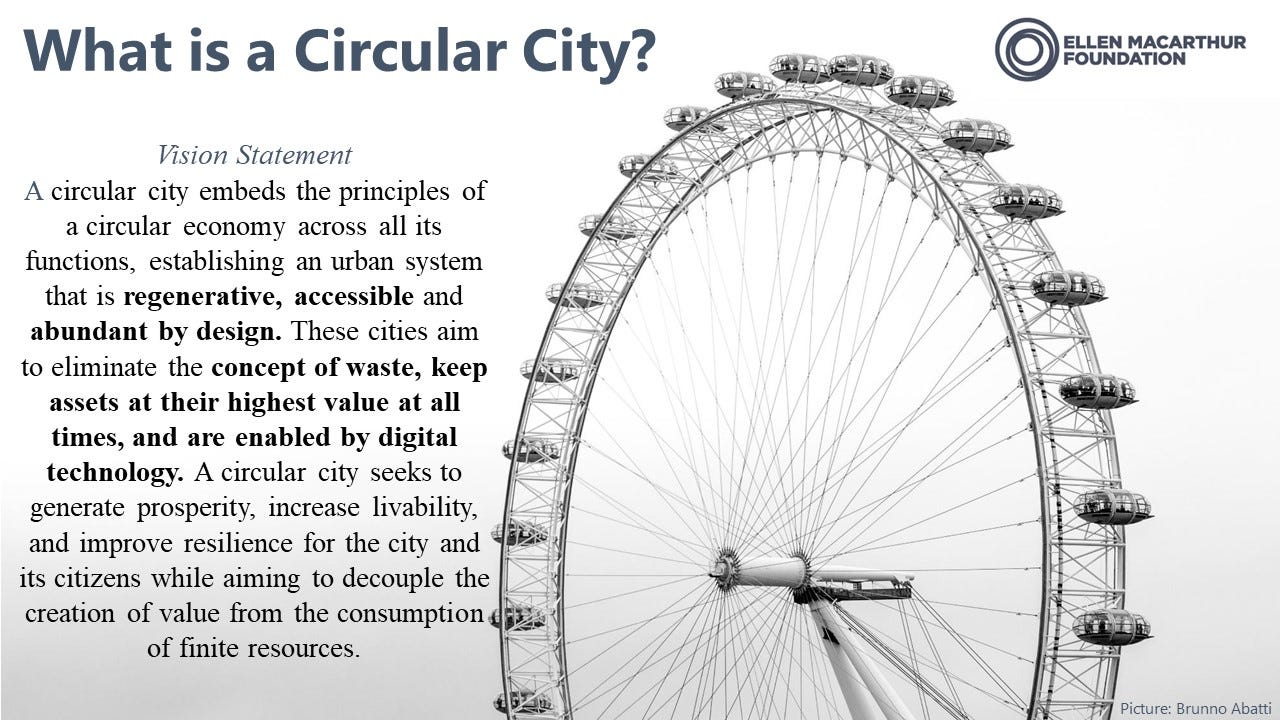

A circular economy approach for a city is interesting at the city-level for a number of reasons. For instance, technical and biological ‘nutrients’ become aggregated within city boundaries and can be found in quantities worth harnessing through urban mining (Li, 2015). In addition, stakeholders are geographically close and this in itself can aid collaboration to close resource loops (Morlett, 2014). In this context, city mayors, committees, and organizations promote certain initiatives that strive to achieve the goals of a sustainable circular economy. While there is no universally accepted definition for a ‘Circular City’ the Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2017) has come up with a vision…

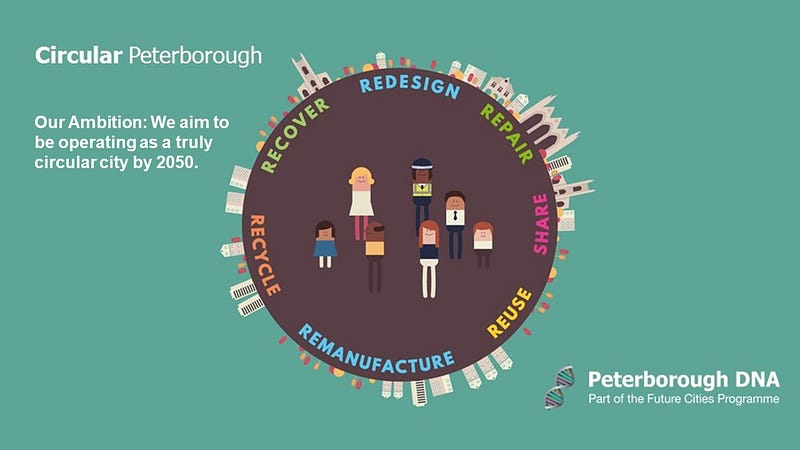

A number of cities in western Europe have shown commitments to the concept of circular city. Most of the cities that are transitioning towards circularity are from Netherlands and the Great Britain. The city of Peterborough has an ambition of being a truly circular city by 2050[1]. Other cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Haarlemmermeer, Glasgow were also in the preliminary phase of implementing circular economy strategies (Prendevillea, Cherim, & Bocken, 2017).

The concept of the “Smart City”, on the other hand, has been gaining ground for some time and is seen as a vehicle for urban sustainability (Bakıcı et al., 2013; Cocchia, 2014; Bodum, 2015; Caragliu et al., 2011; Hollands, 2008). The smart city movement is concerned with gathering data to monitor and optimize resource use through technology, and has been a key concept of the Circular Economy narrative (Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2017). According to the (Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India, 2018), which is responsible for implementing the urban renewal and retrofitting program in 100 cities in India under the program ‘ Smart Cities Mission’ — a smart city is one that “provides for the aspirations and needs of the citizens, and where urban planners ideally aim at developing the entire urban eco-system represented by the four pillars of comprehensive development-institutional, physical, social and economic infrastructure.”

As India invests in long-term infrastructure to improve citizens’ quality of life through this mission, it could incorporate circular economy principles into the design of the infrastructure needed to provide water, sanitation, and waste services at scale, creating effective urban nutrient and material cycles. More systemic planning of city spaces, integrated with circular mobility solutions, can contribute to higher air quality, lower congestion, and reduced urban sprawl. Flexible use of buildings and urban spaces, enabled by digital applications, can increase utilization rates, getting more value out of the same assets. Higher efficiency and lower overall building and infrastructure costs could also help meet the housing needs of the urban poor without compromising safety and quality (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016)

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016 report shows that a circular economy path to development could bring India annual benefits of ₹40 lakh crore (US$ 624 billion) in 2050, compared with the current development path — a benefit equivalent to 30% of India’s current GDP. The report’s conclusion rests on high-level economic analysis of three focus areas key to the Indian economy and society — cities and construction, food and agriculture, and mobility and vehicle manufacturing. The assumption that the Indian businesses should lead the way in the transition phase, with policymakers simultaneously setting the direction and creating the right enabling conditions could be discussed further. The transformation from a linear to a circular economy would require not only environmental but also social and economic restructuring of production and consumption patterns. Such systemic restructuring would involve several actors (Chaturvedi, Gaurav, & Gupta, 2017).

In the next posts, I would like to explore how cities across the globe are adopting circular economy as a strategy and also attempt to provide ten recommendations for city managers on how they could start the process of a “Circular Economy Transition” in their own city.

Footnote

[1] http://www.futurepeterborough.com/circular-city/circular-peterborough-commitment/

References

Bakıcı, T., Almirall, E., Wareham, J., 2013. A Smart city initiative: the case of Barcelona. J. Knowl. Econ. 4, 135–148.

Bodum, L., 2015. Developments within geospatial technologies for the support of urban sustainability towards smart cities. In: Onsrud, H., Kuhn, W. (Eds.), Advancing Geographic Information Science: The Past and Next Twenty Years. GSDI Association Press, Needham, MA, pp. 259–264

Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., Nijkamp, P., 2011. Smart cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 1 (8), 45–59.

Cocchia, A., 2014. Smart and digital city: a systematic literature review. In: Smart City. Springer International Publishing, pp. 13–43.

Chaturvedi, A., Gaurav, J. K., & Gupta, P. (2017). The Many Circuits of a Circular Economy. Brighton: STEPS Centre.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2016). Circular Economy in India: Rethinking growth for long-term prosperity. Cowes: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Ellen Macarthur Foundation. (2017). Cities in the Circular Economy: An Initial Exploration. Cowes, Isle of Wight: Ellen Macarthur Foundation. Retrieved 03 12, 2018, from https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Cities-in-the-CE_An-Initial-Exploration.pdf

Khanna, P. (2018, 03 12). How much economic growth comes from our cities?Retrieved from World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/how-much-economic-growth-comes-from-our-cities/

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India. (2018, March 12). What is a Smart City. Retrieved from Smart Cities Mission : http://smartcities.gov.in/content/innerpage/what-is-smart-city.php

Prendevillea, S., Cherim, E., & Bocken, N. (2017). Circular Cities: Mapping Six Cities in Transition. Environmental Innovation and Social Transitions, 26, 171–194.

Puutio, T. A. (2018, 03 12). Here are 5 predictions for the future of our cities. Retrieved from World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/here-are-5-predictions-for-the-cities-of-the-future