Digitalisation and climate change are two important factors that have many influences on how we live, plan and build our cities. Industrial production processes account for about a third of greenhouse gases worldwide and in Europe only about 40% of the materials are recycled or reused. The circular economy is not about einen manufacturer converting einen product, but identifying, analysing and systematically linking production and (urban) infrastructure systems.

In 2018, we took part in the evaluation of student projects for “Urban Metabolism Prototypes”, an urban design course at TU Berlin. The course was designed to provide a structured approach to circular economy thinking. Prototypical solutions for different urban systems, such as waste & recycling, water as a resource, food & urban greenery or sustainable building methods were developed. Throughout the projects, students touched upon diverse and inspiring ideas, experimenting with Berlin as an urban playground applying the concept of Circular Economy by solving water challenges, bio-waste issues, public toilet and nutrients circulation. The results gave us inspiration to see how young architects can shape the concept and solve the urban challenges of the 21st century with the use of Circular Economy.

The topic of water was prominent and solutions were developed from different angles.

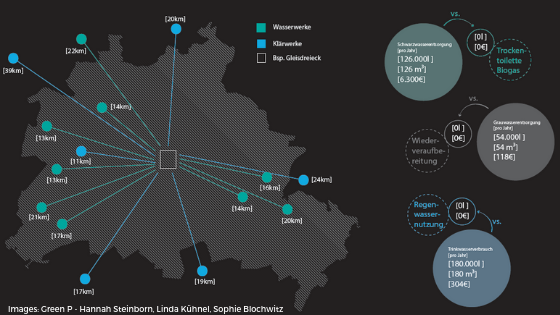

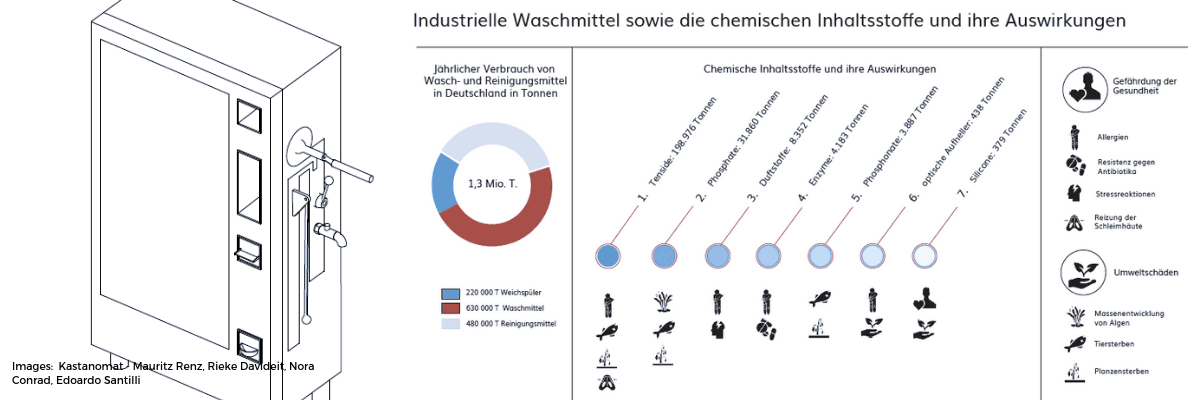

With the Green P project Hannah, Linda and Sophie wanted to set a statement regarding the waste of resources on a daily basis through the current unsustainable public toilet system in Berlin. Another project called Urban Reef addressed the issue of Berlin’s water quality deterioration, looking at the Spree river. Berlin operates to a large extent on a combined sewer system, rainwater overflow leads to wastewater finding its way into the Spree or Landwehrkanal, mentioned Till, Mara, Louisa and Laura. 70 percent of the water that runs through Berlin is being enhanced to drinking water by bank filtration. Every bit of waste or pollutants we dispose improperly influence our drinking water, and surrounding flora and fauna. Nora, Edoardo, Rieke and Mauritz also looked at the challenges around water issues through the project Kastanomat. The daily usage of potable water from a single person is between 100-120 liters, whereas just 3 liters are drinking water. It goes along with challenges of water scarcity, affecting our planet. Furthermore our rivers and oceans are extremely polluted, partially because of the chemicals used for the traditional laundry. Another project that was selected is called Energy Cube that works with bio-waste on a local level. This idea promotes a decentralised system for local energy production.

No doubt that the bio-loops are an inevitable part of circular systems, if they are designed correctly. Bio waste is well suited to be recycled into biogas and compost that can be used as fertilizer. In the sense of a circular economy, the waste could be recycled locally and consequently produce local energy. As for the water system, there could be many diverse approaches for circular economy methods. With the project Green P, a decentralised toilet system was developed, as it is not connected to the urban water system and does not require such water consumption. Green P also reuses rainwater in a closed cycle. This projects gives an alert for waste as resources by reusing every part of the produced organic matter. Another project called Urban Reefs proposes making the circular approach run more smoothly by further circular measures to improve running cyclical systems. For example, using recycled materials and applying natural filtration processes. However, even if it is a cyclic system, humans dispose polluted water back into the environment, which ultimately has to be treated making the process extra costly. The Kastanomat Projekt proposes to stop the use of chemical detergents and supplementing it with plant based, 100% biodegradable ones. The key element students used and scaled for the whole urban water treatment was chestnuts that contain saponins, a soap-like chemical compound. This approach to the water treatment has its circular methods combining a nature-based treatment system into current not fully perfectly engineered water cycles. By reviewing those projects, we can conclude that circular economy is not only about closing the loop but also about bringing improvement and innovation into already existing cycles.

Even though circular economy sounds like an appealing approach, it remains extremely challenging to bring it to the urban context. Hannah, Linda and Sophie mentioned that they faced a challenge to narrow down a problem in a system and cut off an integrated process from its necessary resources. The bigger the urban surface you want to touch, the exponentially bigger the networks in which it is woven. This is why they singled out the project of public toilets in Berlin and turned them into a self-sufficient and decentralised system. Decentralised solution for the bio-waste treatment were also the answer for Energy Cube to cope with similar challenges. Here, people have the responsibility for running the facility and at the same time taking advantage of the decentralised electricity production recovering directly into the electricity grid of their homes. However, it is not only about the system but the people who create it. In order to make circular economy work probably the most vital thing is to make people rethink and reevaluate their behavior. There wouldn’t be a point in trying to clean urban waters without tackling the main cause of pollution, which is a lifestyle that distinguishes itself by relying on unsustainable habits, modes of transportation, and industry. Another question is to what extent people are open to the new environmentally friendly possibilities to cope with the necessities of our everyday life, instead of simply relying on the conventional ones – behavioural change!

All groups answered with YES!

The more resources we reuse and the more we get out of a single resource, the better for coming generations. Urban planning and architecture can play an extremely important role by laying the foundation for circular cities. Therefore, architects and urban planners should be aware of their responsibility for circular thinking. (Green P)

The human behavior is having a much bigger impact on the planet than we like to admit. The building industry is affecting our environment greatly. It is extremely necessary for urban planning and architecture to focus on the circular economy. The main agenda is to build as environmentally friendly as possible. (Urban Reef)

It is important! As architects, we work in long-term projects like buildings, which are going to be there 60 or more years. It seems like recycling is not part of this process but concrete and bricks will reach the end of life one day. Hence, architects should always use products that are not just looking good and have good structural features but also are sustainable concerning environment and sustainability. (Energy Cube)

Architecture is seen by far as too static, only due to its durability for a few years. If we look at the concrete buildings or bridges from the last century, thousands of buildings need to be renovated. And even if concrete is, at least partially, recyclable, the current building system is one of the top CO2 emitters in the world. Therefore, we need building materials that are not only producible with far less emissions but fit even better into a circular economy, like wooden buildings for example. (Kastanomat)

Educational formats like this contribute to more consciousness about the topic of circular economy and connected to that urban resource efficiency and climate change. It was remarkable to see the high degree of interdisciplinary thinking and how the students hacked existing supply chains in order to create more circular urban systems.

And all the students who contributed with their answers:

Green P – Hannah, Linda and Sophie

Urban Reef – Till, Mara, Louisa, Laura

Energy Cube – Jule, David, Lauritz, Theresa

Kastanomat – Nora, Edoardo, Rieke and Mauritz